(New Yorker) In the magazine earlier this month, I wrote about Greg Chung, a Chinese-American engineer at Boeing who worked on NASA’s space-shuttle program. In 2009, Chung became the first American to be convicted in a jury trial on charges of economic espionage, for passing unclassified technical documents to China.

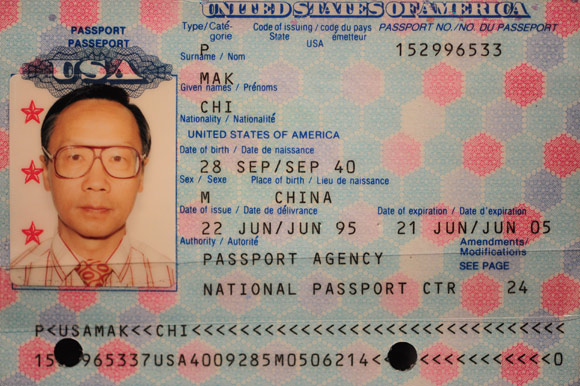

While reporting the story, I learned a great deal about an earlier investigation involving another Chinese-American engineer, named Chi Mak, who led F.B.I. agents to Greg Chung.

The Mak case, which began in 2004, was among the F.B.I.’s biggest counterintelligence investigations, involving intense surveillance that went on for more than a year.

The stakes were high: at that time, the F.B.I. did not have a stellar record investigating Chinese espionage.

Three years earlier, the government had been publicly humiliated by its failed attempt to prosecute the Chinese-American scientist Wen Ho Lee on charges of passing nuclear secrets from the Los Alamos National Laboratory to China, in a case that came to be seen by some observers as an example of racial prejudice.

The investigation of Chi Mak—followed by the successful investigation and prosecution of Greg Chung—turned out to be a milestone in the F.B.I.’s efforts against Chinese espionage, and demonstrated that Chinese spies had indeed been stealing U.S. technological secrets.

While Chung volunteered his services to China out of what seemed to be love for his motherland, the F.B.I. believed that Mak was a trained operative who had been planted in the U.S. by Chinese intelligence.

Beginning in 1988, Mak had worked at Power Paragon, a defense company in Anaheim, California, that developed power systems for the U.S. Navy.

The F.B.I. suspected that Mak, who immigrated to the U.S. from Hong Kong in the late nineteen-seventies, had been passing sensitive military technology to China for years.

The investigation began when the F.B.I. was tipped off to a potential espionage threat at Power Paragon.

The case was assigned to a special agent named James Gaylord; since the technologies at risk involved the Navy, Gaylord and his F.B.I. colleagues were joined by agents from the Naval Criminal Investigation Service.

Mak was put under extensive surveillance: the investigators installed a hidden camera outside his home, in Downey, California, to monitor his comings and goings, and surveillance teams followed him wherever he went. All of his phone calls were recorded.

A short and energetic sixty-four-year-old with a quick smile, Mak was a model employee at Power Paragon.

Other workers at the company often turned to him for help in solving problems, and Mak provided it with the enthusiasm of a man who appeared to live for engineering.

His assimilation into American life was limited to the workplace: he and his wife, Rebecca, led a quiet life, never socializing with neighbors.

Rebecca was a sullen, stern woman whose proficiency in English had remained poor during her two and a half decades in the United States. She never went anywhere without Mak, except to take a walk around the neighborhood in the morning.

Sitting around the house—secret audio recordings would later show—the two often talked about Chinese politics, remarking that Mao, like Stalin, was misunderstood by history.

The influence of Maoist ideology was, perhaps, evident in the Maks’ extreme frugality: they ate their meals off of newspapers, which they would roll up and toss in the garbage.

Every Saturday morning, after a game of tennis, they drove to a gas station and washed their car using the mops and towels there.

From the gas station, the Maks drove to a hardware store and disappeared into the lumber section for ten minutes, never buying anything.

For weeks, the agents following them wondered if the Maks were making a dead drop, but it turned out that the lumber section offered free coffee at that hour. . . . (read the rest)

You must be logged in to post a comment.